Cities are all about flow – what enters and what exits. Maybe hundreds of people get off the train every day, maybe even more board a plane to leave. Food and goods are shipped in or out, carried on trucks speeding along the interstate. Weather systems converge or diverge, perhaps moving in from the north, picking up drier air, and moving on southward. Exciting new things are bought, used, and thrown away – and our trash travels far and wide across the country. Energy flows in and out too, but it’s easy to throw off balance.

We all live under an energy budget. We receive energy from the sun and our surroundings, and eventually radiate a certain amount of it back out. The entire Earth does this with solar radiation on a much larger scale. A city or forest or desert or farm is heated from sunrise until sunset. We frequently end up with a temperature lag – we’ve received more energy than can radiate out at the same rate, so the latter half of the day tends to be hotter. This applies to larger geographic areas and timescales, as well. For example, during northern summer the North Pole is in an energy surplus while it points towards the sun, but in northern winter it goes into an energy deficit. But what happens when we alter these natural cycles?

Cities easily alter the flow of energy, trapping heat and causing loud complaining. Having spent many summers in Washington, DC, grumbling about the heat was almost an hourly activity for many of us working downtown. “It was never like this before!” and “This must be the hottest summer ever!” were frequent comments said to no one in particular on the scorching sidewalks. Certainly many would agree that we are gradually warming much of our world. But that was not the main problem causing these complaints on crowded Metro platforms. If I wanted to cool off just a bit, I could go sit by any of the monuments – they all have open, grassy areas with shade trees and beautiful gardens.

So why do cities get so hot? Why do we call them urban heat islands? And why do people seem to instinctively flock to city parks blanketed in bright, green grass and landscaped shrubbery when they’re overheated?

Salt Lake City is a prime example of urban heating. Our office buildings trap more than just people. We talk about our majestic seven canyons, but buildings create their own more disappointing urban canyons. Similarly to the rock walls of a real canyon, the walls of tall buildings provide excellent surfaces to absorb and reflect heat in odd directions. They block this energy from making a timely exit, and we feel it for longer than we normally would. Buildings are obstacles – heat takes longer to find a way out, and pleasant, cool breezes can’t always find their way in. Furthermore, cities are frequently built from materials that don’t reflect the sun’s radiation very efficiently. Asphalt and concrete absorb instead of reflect heat – and start rumors of egg-frying capabilities.

Salt Lake City from 300 West to the Wasatch foothills – red and white show hot buildings/paved surfaces, blue and green show cooler vegetation. Satellite image from NASA.

But there is another major problem. Where there is asphalt, there is a lack of vegetation. Where there is no vegetation, there is no evapotranspiration. Water vapor evaporating off of plants and soil cools the air. Salt Lake has a dry climate, and stands to benefit even more from increased vegetation. However, there is a balance that must be struck here between water conservation, cost, and energy savings. Drought-tolerant plants are great, and native shade trees are even better. Urban heat islands can actually worsen water quality – hot pavement can increase the temperature of rainwater, which eventually runs off and drains into larger bodies of water where the higher temperature can then have negative effects on aquatic life. This is a good example of the long reach of anthropogenically altered environments. Many of us probably do not immediately consider how our tall buildings could be killing distant aquatic ecosystems.

Furthermore, mitigating the effects of urban heat islands will also help conserve energy. If we use vegetation to cool a city, there will be less of a demand on cooling systems. High usage of air conditioning releases even more heat into the air and degrades air quality – something which Salt Lake City certainly does not need to get any worse.

Myron Wilson, the Director of the Office of Sustainability, has a background in architecture. He summarizes the problem: “Urbanization and the proliferation of dark or non-reflective surfaces, like asphalt and concrete, has led to an increase in city temperatures – as much as 2-8 degrees above the surrounding area. This urban heat island effect results in less pleasant spaces for humans, as well as increased energy loads for ventilating and air conditioning. In addition, the changes impact wildlife habitat and native plants in and around our cities. By integrating green and natural spaces into our urban environments, we can lessen these negative impacts and simultaneously create more beautiful spaces in which to live, work and play.”

In fact, Salt Lake City’s urban heat island has been studied extensively by the EPA. It was featured in the Urban Heat Island Pilot Project (opens as PDF), which ran from 1998 – 2002. The project found several opportunities for improvements – we could increase tree cover by 13%, and we have many areas where different building materials could be used to increase reflectivity. For a while, the city took part in a Cool Communities Program, which aimed to educate the public on ways to reduce the effects of an urban heat island. Tree Utah still works hard on this by gathering volunteers to plant trees and help teach others. Tree Utah understands that planting more trees provides many benefits, and cooling a city is one of them: “Trees lower air temperatures by releasing water vapor through their leaves and shade trees can make buildings up to 20 degrees cooler.”

It is becoming ever more important that we do not view nature and cities as distinctly separate places. The Urban Green Spaces Institute puts it this way: “…unless we create cities that are both livable and loveable, it will be impossible to protect the rural landscape and wilderness areas that have been the primary focus of the conservation movement’s efforts to protect the environment. It is our belief that the nation’s conservation ethic has been largely predicated on the philosophy that nature is ‘out there’ beyond the city and that too little effort has been expended to protect nature and provide Greenspaces where over 80% of our population lives, in the city.”

So how do we stop thinking of nature as a place we only go for vacation, a place from which we must return? Cities have wildlife, but we think of it as pests. Cities have vegetation, but we think of it as decoration. And cities certainly live under the same sun that a desert or a forest does. As residents of Washington, DC know all too well the heat waves that have recently been increasing in frequency can be deadly. Better integration of nature into urban areas can benefit human health – both physical and mental. Who doesn’t feel calmer and happier sitting under a tree in an attractive city park than surrounded by a concrete jungle?

A green roof on the Chicago City Hall helps cool the area and the building. Photo from DOE/NREL.

The built and the natural environments are not separate and they never have been. What we do in our cities can have profound, far reaching effects on places and lives that we have never considered. I believe this is part of a larger disconnect many people feel from nature – that we have to keep it separate from us, because we have to control everything about our lives. And nature represents a distinct lack of control, with forces that we don’t always fully understand. It is time to accept that we are part of this, we are part of a system more dynamic than we realize. Let’s not emphasize our glaring disconnects anymore, let’s find and strengthen forgotten connections. Let’s green our urban spaces.

And maybe this will slow the rabid complaining about the heat.

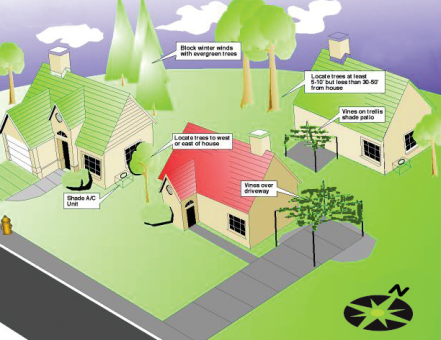

If you want more information on what you can personally do, the EPA has strategies for mitigation and getting involved at the community level. Residentially, if you’re moving into a new space or altering your yard, think about strategically planting trees to help bring down your energy costs:

Most of all: consider what enters and exits your city, and how far it might go.

Annie Gilliland is a Master’s student in the Environmental Humanities graduate program at the University of Utah. She is working on a fellowship with the Office of Sustainability.